|

CHAPTER III: An Introduction to Afghanistan

SECTION I: LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION

Lying more than 482 kilometers (300 miles) from the sea, Afghanistan is a

barren, mostly mountainous country of about 647,500 square kilometers (250,000

square miles). It is bordered by Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan to the

north, Pakistan to the east and south, and Iran to the west. Including a long,

narrow panhandle (the Wakhan Corridor) in the northeast, Afghanistan has a

northeast-southwest extent of about 11,450 kilometers (900 miles), and a

northwest-southeast extent of about 804 kilometers (500 miles). With peaks up to

about 7315 meters (24,000 feet), the Hindu Kush forms the spine of the country,

trending southwestward from the Pamir Knot to the central Afghan province of

Bamian. Subsidiary ranges continue to the south and the west with decreasing

elevations, gradually merging into the plains that continue into Iran and

Pakistan. A broad plateau stretches from north of the Hindu Kush to the Amu

Darya River and eventually to the Russian steppes. In the east, the mountains

are indistinguishable from those of Pakistan. Afghanistan is approximately the

size of Texas.

SECTION II: TOPOGRAPHY

About one-third of Afghanistan, in the southwest and north, is arid plain.

The southwestern plain is the larger of the two and is a barren desert with

large areas of drifting sand, scattered hill belts, and a few low mountains.

Small villages along a few intermittent streams, small settlements, and a narrow

band of cultivation along the Helmand River are the only features that break

desolation. The Helmand is one of the few perennial streams in the region. The

northern plains are actually steppes with seasonal grasslands supporting a small

nomadic population. Permanent settlements are located along the margin of the

steppes and on the flood plain of the Amu Darya River.

The mountains that comprise the other two-thirds of the country are the

perennially snow-capped Hindu Kush in the northeast and progressively lower

mountains in the west. The Hindu Kush have sharp-crested ridges and towering

peaks, while the lower, western mountains are generally rounded or flat-topped.

Afghanistan can be broken down into three military operational zones: the

Northern Steppe, the Afghan Highlands, and the Southwestern Desert Basins.

SECTION III: DRAINAGE

Afghanistan has four major river systems that originate in the Hindu Kush:

the Kabul, the Helmand, the Amu Darya, and the Harirud. Of the four, only the

eastward flowing Kabul ever reaches the ocean; the other three eventually

disappear into salt marshes or desert wastes. Only the Amu Darya (also known as

the Oxus) has significant navigable reaches. The rest are fordable for the

greater part of the year throughout their courses. The Amu Darya also serves as

the northern border of Afghanistan. The Helmand is the largest in flow and

volume and runs southward into across the southern desert into the salt marsh

wastes found along the Afghan-Iranian border. The Harirud runs westward past

Herat then turns northward, forming the border between Afghanistan and Iran.

All the Afghan rivers and their tributaries are used for irrigation.

Supplementing the stream irrigation is the karez, a system of underground

channels (with vertical access and maintenance shafts) carrying water from the

base of the mountain slopes to oases on valley floors. The signature of karez

(qanat in Iran), particularly noticeable from the air, is the row of evenly

spaced openings (shafts) surrounded by mounds of earth that define the course of

the underground channels.

SECTION IV: VEGETATION

What little natural vegetation there is in Afghanistan consists mainly of

bunch grasses; trees are scarce and mostly limited to planted poplars and

willows around settlements. Because of infertile soils and centuries of seeking

fuel and forage, even scrub and brush are difficult to find. Timber is mostly

absent. Any timber laying around the ground or attached to buildings in deserted

villages should be suspect for booby traps. Timber is very scarce and villagers

will booby trap their homes to prevent theft and pilferage.

Irrigated areas produce wheat, barley, corn, and rice, as well as sugar

beets, melons, grapes, cotton almonds, and deciduous fruits. The two primary

Afghan cash crops are opium poppy and cannabis. Afghanistan is the major opium

supplier for the European heroin market.

SECTION V: CLIMATE

Marked seasonal extremes of temperature and scarcity of precipitation

characterize Afghanistan’s climate. Topographic features strongly influence all

elements of the climate. Winters (December through February) are dominated by

constantly changing air masses associated with passing migratory lows and

frontal systems. Winters are cold, with nighttime temperatures below freezing

common in low elevations and frequent winter snows at higher elevations. To the

south and southeast the low-level temperatures are less severe. Winter snows are

frequent at the higher elevations and there are permanent snowfields in the

Hindu Kush. Summers (June through August) are continuously sunny, dry, and

severely hot; however, intrusions of moist, southerly monsoon air occasionally

bring rain, increased humidity, and cloudiness to the extreme eastern portions.

At elevations below 1,220 meters (about 4,000 feet) temperatures rise to over

38oC (100oF) on a daily basis. Very low humidity is normal

during the summer. In the other seasons, relative humidity is high in the early

morning and moderate in the afternoon over most sections. In most of

Afghanistan, winter and spring are the cloudiest periods, and clear skies are

common in summer.

Precipitation is scarce, with desert conditions prevailing in the

southwestern and northern plains. What annual precipitation there is falls

mostly in the winter and spring; summers are almost uniformly rainless.

Thunderstorms are most frequent during the spring, but also occur during summer

in extreme eastern portions of the country. Flash floods sometimes result from

severe thundershowers. Long droughts are not uncommon.

SECTION VI: THE ECONOMY

Afghanistan is one of the world’s poorest and least developed countries. The

geographical location of Afghanistan contributes to many of its features:

abundance of natural resources such as natural gas, petroleum, coal, copper, and

precious and semiprecious stones; varied but landlocked topography with mostly

rugged mountains, especially in the northeast, and plains in the north and

southwest; earthquakes and flooding; ethnic diversity; and a variety of

languages.

The Taliban, preoccupied by its determination to defeat the Northern

Alliance, did little to rebuild Afghanistan, which has been in economic disarray

since the end of Soviet occupation in 1989. Two decades of war and grinding

poverty have left Afghanistan in disrepair: Warfare has destroyed roads,

bridges, and canals, while looting and shortages of spare parts has shut down

power plants, factories, and telephone systems. Afghanistan has some of the

worst social indicators in the world: the highest rates of illiteracy; mother,

child, and infant mortality; malnutrition; and ratio of widows and orphans in

the population. These combine to produce one of the lowest life expectancies on

the globe. The bleak situation has prompted foreign aid efforts, such as the UN

World Food Program, which provides assistance during periods of drought.

SECTION VII: POPULATION FIGURES AND DISTRIBUTIONAfghanistan’s

population, estimated at 26,813,057 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001) is characterized

by high growth, low quality of life, and an unusual settlement pattern brought

on by conflict and drought. The country is extremely young, with 42 percent of

the population under the age of 15. Life expectancy is under 40 years,

reflecting the overwhelmingly poor living conditions throughout the country. The

majority of the people (about 60 percent) live in rural areas, about 30 percent

live in cities, and 10 percent live a nomadic lifestyle. These percentages are

rough estimates, however, because the ongoing civil war and a succession of poor

growing seasons have forced over 3 million Afghanis to become refugees. Between

600,000 and 800,000 people were internally displaced as of the end of 2000,

according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. The UN

High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that 2.5 million Afghanis have migrated

out of the country.

SECTION VIII: ETHNICITY AND LANGUAGE

Afghanistan is a complex mosaic of ethnolinguistic groups. The dominant

group, politically and in terms of numbers, has been the Pashtun, who consider

themselves the “true” Afghani people. Pashtuns are Sunni Moslems, tribally

organized, speak Pashtun, and comprise between 35 and 50 percent of the

population. The Pashtun live primarily in the south and east areas of

Afghanistan, which include the cities of Kandahar and Kabul, respectively.

Throughout Afghanistan’s history, tribal rivalries have characterized the

Pashtun people, but tribes have tended to put aside such differences when faced

by a common enemy, such as the British in the 19th century and the Soviets in

1979.

The Tajiks are the principal ethnic group of Afghanistan’s northeast. Tajiks

comprise about 25 to 30 percent of the population and are defined as Sunni

Moslems who speak Dari, a derivative of Farsi. Animosity between the Tajiks and

Pashtuns has been a hallmark of internal politics since the British were driven

out in the 19th century.

The Hazaras, who make up about 15 percent of the population, are concentrated

primarily in the center of the country. Hazaras are characterized by Mongoloid

features and practice the Shia variety of Islam. Historically, the lowest group

on the Afghan social ladder, the Hazaras have endured discrimination and poor

living conditions for centuries. Most are engaged in agricultural activities.

The final large ethnic group in Afghanistan are the Uzbeks, whose numbers

have diminished in recent years as many have migrated to Uzbekistan. Located

primarily in the north-central section of the country, the Uzbeks speak Uzbeki

and comprise about 10 percent of the national population.

SECTION IX: RELIGION

As of 1979, 99.7 percent of the Afghan population was of the Moslem faith,

and the remainder was largely Hindu. In Taliban-held areas, Islam was the

dominant force in everyday life, imposing a draconian form of sharia law. Under

this legal system, all tenets of the Muslim faith were adhered to, or a

punishment was meted out. Religious police carried small whips, which they used

to publicly flog people if some aspect of their appearance or behavior was not

in compliance with Muslim law. Hangings took place on a regular basis. Women

were not allowed to receive an education and only worked outside the home if

they were involved in health services. Conversion to another faith could be

punishable by death. There was an initiative on the part of the ruling Taliban

to make Hindus wear identity badges – ostensibly to protect them from the

religious police.

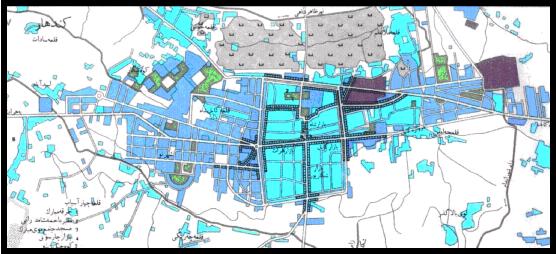

SECTION X: KEY CITIES

Kandahar. Kandahar is located is southern Afghanistan, approximately

500 kilometers (310 miles) southwest of Kabul and 90 kilometers (56 miles)

northwest of the Pakistan border. The city lies at the northeast corner of the

vast, nearly uninhabited Dasht-i Margow. Kandahar is in an area of subtropical

steppe. Sand ridges and dunes alternate with expansive desert plains. There are

also areas of barren gravel and clay where sparse vegetation and low growth

prevail. Kandahar’s population is estimated at 329,300 (U.S. Census Bureau,

2001).

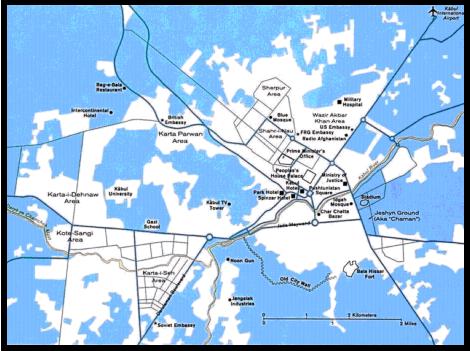

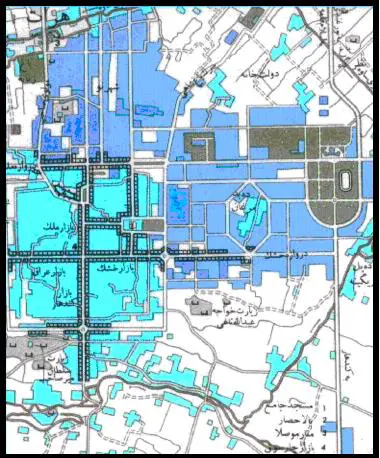

Kabul. Kabul is located in northeastern Afghanistan on the banks of

the Kabul River. The city spreads out on the north and south banks of the river

and is further separated into northern and southern sections by a series of low

hills. The Kabul River flows from southwest to northeast and through the water

gap known as “Lion’s Gate,” which divides the hills. Elevations range from 1,789

meters above sea level at Kabul International Airfield to 2,219 meters at Kohe

Sher Peak near the city center. Several small streams flow in from the west,

joining to form the Cheltan River, which, in turn, joins the Kabul River just

south of the Lion’s Gate. The Logar River flows north to join the Kabul River in

eastern Kabul; Khargz Lake, about 20 kilometers west of central Kabul, is the

only lake in the region. There are, however, several small marshes scattered

across the northeastern half of the city and environs. Soils on the mostly flat

plains around Kabul are deep silty sand, clayey sand, and gravels that are fair

to good in over-all suitability for construction purposes. On hill slopes,

bedrock outcrops comprise half or more of the surfaces.

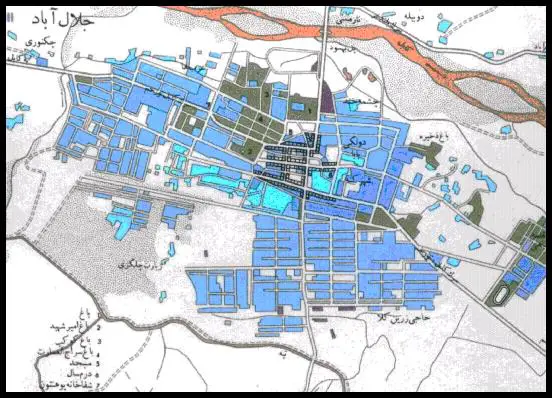

Jalalabad. Jalalabad is the largest urban center in eastern

Afghanistan between Kabul (125 kilometers [78 miles] to the west) and the

Pakistan border at the Khyber Pass (75 kilometers [47 miles] to the east). The

city has been an important commercial, telecommunications, and cultural center,

and has a population of 154,200 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001). The city dominates

the entrances to the Laghman and Kunar valleys and is a leading trading center

with India and Pakistan. Oranges, rice, and sugarcane grow in the fertile

surrounding area, and the city has cane processing and sugar refining as well as

papermaking industries.

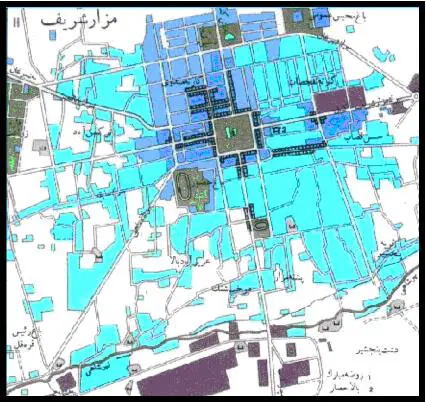

Mazar-e Sharif. Mazar-e Sharif, the provincial capital of the Balkh

Province, is situated on the main route between Kabul and the Termiz,

Uzbekistan. Historically, its importance was twofold: it was 70 kilometers (43

miles) south of the Soviet Union, and it was a center for Afghanistan’s

fledgling oil industry. Its population is estimated at 232,800 (U.S. Census

Bureau, 2001).

Herat. Herat is centered in western Afghanistan on the flat river

plains a few kilometers north of the Harirud River. The Iran border is

approximately 120 kilometers (75 miles) to the west, Turkmenistan 110 kilometers

(68 miles) to the north, and Kabul is approximately 650 kilometers (400 miles)

to the east. Elevations within the city range from roughly 920 meters (3,018

feet) ASL in the south to 960 meters (3,150 feet) ASL in the north. Mountains

ranging in height from 1,800 meters to 3,300 meters (about 6,000 to 11,000 feet)

surround the city. Earthquakes and tremors are common occurrences. Herat

experiences a hot, north-northwesterly wind from May to September. This wind

blows constantly, but is particularly strong in the afternoon; wind velocity is

typically around 50 miles per hour (43.5 knots), with gusts up to 80 miles per

hour (69.5 knots).

SECTION XI: CULTURAL FACTORS

Even though ethnicity has only recently surfaced as a central issue, ethnic

divisions and internal colonization have existed in Afghanistan for the last 250

years. Since Ahmad Shah Durani founded the Afghan state in 1747, various

Pashtun-dominated regimes (monarchic, republican, communist, Islamist) have used

the powers and institutions of the central government to colonize the

non-Pashtun ethnolinguistic areas. To this end, Pashtun regimes tried various

Pashtunization measures (political, educational, linguistic, economic,

demographic, social, and economic) to suppress and weaken other ethnic

communities and their hold on territories and to ensure Pashtun supremacy and

domination.

Pashtun domination ended with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979,

when Babrak Karmal, leader of the Parcham faction of the People's Democratic

Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), became president. The Parcham, unlike the Khalq

faction, was composed mostly of non-Pashtuns. The Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, and

other minority ethnic groups were allowed equal participation in politics,

education, economics, and other aspects of life in the Afghan communist

government. Under its so-called nationalities policy, minority languages and

dialects – such as Hazaragi, Uzbeki, Baluchi, Pashai, and others – began to

flourish, and Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, and other minority ethnic groups were

appointed to positions in the foreign ministry, including diplomatic posts

abroad, as well as in the Ministries of Defense and Interior.

These opportunities changed the balance of power for the minority ethnic

groups inside Afghanistan. By the time the Soviet forces withdrew in 1989, there

were many more Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, and other minorities than ever before

serving as pilots, engineers, doctors, ambassadors, military generals,

ministers, central committee members, governors, university professors, and so

on. One Hazara, Sultan Ali Keshtmand, even became prime minister, something

unthinkable during the Pashtun-dominated regimes in the past.

The situation among the Afghan refugees in Pakistan during the Soviet

occupation was different, however. In Pakistan, the Pashtuns dominated the

Afghan refugee political parties. Of the seven political groups in Peshawar,

Pakistan, only one – the Islamic Society (Jamiyat-e Islami) headed by Burhanudin

Rabani – was non-Pashtun; the others were all Pashtuns, either linguistically or

genealogically. This meant that most of the cash and weapons provided by the

United States, Saudi Arabia, and others went to the Pashtuns, as well as the

lucrative jobs related to the humanitarian assistance agencies and other

organizations helping the Afghan refugees.

When the Islamic groups came to power in 1992, the ex-communists in the

government joined the mujahidin according to their ethnic affiliation. The

Pashtuns sided with Gulabudin Hikmatyar's Islamic Party (Hizb-e Islami) – a

Pashtun party – while the non-Pashtuns supported Ahmad Shah Massoud, a Tajik and

Rabani's military commander, and his Supervisory Council (Shoray-e

Nezar)/Islamic Society (Jamiyat-e Islami). This division established the

parameters for the beginning of a civil war based on ethnic divisions.

In 1994 when Gulabudin Hikmatyar, a Pashtun and the creator of Pakistan's ISI

(Interservices Intelligence) failed to rally the Pashtuns and to seize Kabul

from Tajik Massoud, the Taliban, a Pashtun-dominated Islamic militia said to

have been created and supported by Pakistan and some Arab countries – especially

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – took over the fight for Pashtun

domination. Pakistan, with its own significant Pashtun minority, has been

exploiting the ethnic and sectarian conflict for its own objectives. Iran and

Uzbekistan, and to some extent Tajikistan, feared the Islamic fundamentalism of

the Taliban and assisted the non-Pashtuns with whom they have an ethnolinguistic

and cultural affinity. This has intensified the ethnic conflict in Afghanistan.

Since 1997 some ethnic cleansing has also taken place in which the Hazaras

and the Pashtuns have reportedly massacred thousands of each other's people in

Mazar-e-Sharif, in Bamyan, and in other regions. Also, the Taliban have

reportedly evicted Tajiks from the Shomaly Valley north of Kabul and sent them

to Kandahar along with some Hazaras and other members of minority ethnic groups.

There are reports that the Taliban have brought Pashtuns to settle on the land

and in the houses taken from dislocated Tajiks, Hazaras, and others.

SECTION XII: NATIONISM AND NATIONALISM

The ethnic issue poses problems of terminology. The words “nation” (mellat)

and “nationality” (melliyat) with their European origin do not have the same

meaning in the Afghan context or among the various ethnic groups. In the West,

“nation” implies citizenship and refers to a “community of people composed of

one or more nationalities and possessing a more or less defined territory and

government,” it has a completely different meaning to the Afghan ethnic groups.

To the Pashtuns, “nation” subsumes a combination of notions, encompassing

geography, ancestry, language, religion, culture, and nation-state. In the

Pashtuns' view, the Afghan nation refers to those people who originally settled

near the Suleiman Range and spread to what is now modern Afghanistan and

Pakistan. Pashtun nationalists say “Afghan” also refers to the descendants of

the Prophet Ibrahim. Furthermore, they insist the Afghan nation belongs to the

people who have been speaking Pashto as a native language for many generations.

To the Pashtun nationalists, the Afghan nation also refers to the “real”

citizens of Afghanistan – a “typical” or “true” Afghan is a conservative,

orthodox Sunni Muslim. Most importantly, to the Pashtun nationalists, real

Afghans are those who have Pashtun tribal customs and traditions. This may

explain why their well-known nationalist political party and their newspaper are

both named “Afghan Mellat” and “Afghan Nation” (that is, Pashtun Nation).

According to nationalist Pashtuns, an individual is considered an Afghan if he

possesses “all” of the above qualifications, not just one or two. For example,

speaking Pashto as a native language or being a Sunni Muslim alone does not make

one an Afghan citizen, at least in the eyes of the nationalist Pashtuns.

The non-Pashtuns have their own interpretation of these terms. Unlike the

Pashtuns, they do not identify themselves as a nation (mellat) because they do

not feel they were treated as “real” citizens with equal rights by the

Pashtun-dominated regimes. Instead, they refer to themselves as nationalities

(melliyat) or ethnic groups (qawm). While the word “nation” specifically refers

to territorial boundaries, melliyat identifies a specific group on the basis of

such cultural factors as language, sect, customs, mores, ideals, cultural

habits, and traditions. In the Afghan context, melliyat and qaumiyat are

synonymous and can be translated as “ethnicity,” although melliyat is more

general than qaumiyat because a melliyat can consist of more than one qawm. To

non-Pashtuns, only the Pashtuns are referred to as a nation because they have

had the nation-state and the political system under their control, without

giving equal rights to the minorities. In fact, the Tajiks, Uzbeks, Hazaras, and

other minority groups refer to the Pashtuns as “Afghans.” “Afghanistan”

literally means “the land of the Afghans” (that is, Pashtuns). That is why when

asked about their identity, these non-Pashtun ethnic groups call themselves

“Hazaras,” “Tajiks,” “Uzbeks,” and so on instead of “Afghans.”

In Afghanistan one's loyalty is still first and foremost to the family,

qawm/tribe, sect, and even geography (place of birth) instead of to the “Afghan

nation” as a whole. In the words of one non-Pashtun diplomat, “It is hard to

ascribe any other term [Afghanistan] to [the territory called Afghanistan]

including country, nation, government, and national identity . . . Ethnic,

familial blood determines everything.” The precise ranking of loyalties in a

given situation depends on what is at issue. As a general rule, religion/sect or

ideology supersedes ethnolinguistic group or tribe/qawm. During the Soviet

occupation, all the Afghan ethnic groups united against the communists in a holy

war. After the defeat of the communists, ethnicity became the issue. For

example, when the mujahidin took Bagram military airport north of Kabul in 1992,

the Pashtun communists joined the forces of Gulabudin Hikmatyar, a Pashtun, and

the Tajik communists joined Ahmad Shah Massoud.

SECTION XIII: DANGEROUS PLANTS AND ANIMALS

Afghanistan has a number of large mammal species that could pose a threat to

U.S. personnel. Brown bears, Siberian tigers, and several species of leopards

inhabit the mountains and foothills. Wolves, striped hyena, jackal, wild pigs

and wild dogs are widespread. In addition, soldiers should expect to encounter

numerous venomous reptiles, insects, and plants.

|